The American banking system had been primarily a domestic one throughout its early development. Despite, or because of, the rapid growth in the later 19th century, banking was orientated almost entirely inward to finance the needs of that growth. But as a growing national as well as industrial power, the US adopted several measures early in the 20th century to entice domestic institutions into the foreign money trade.

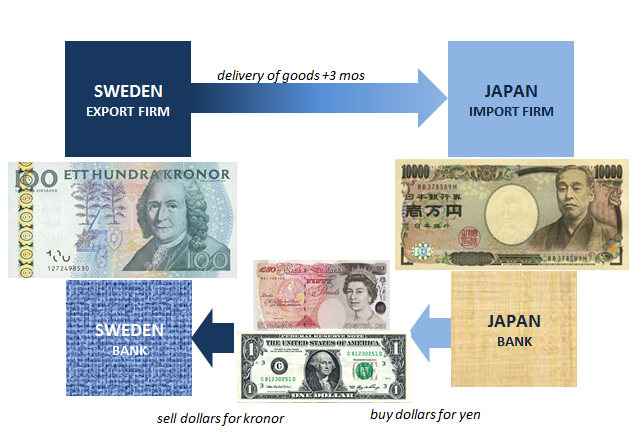

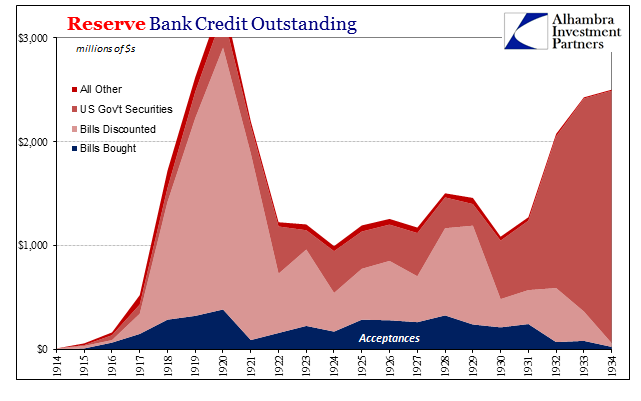

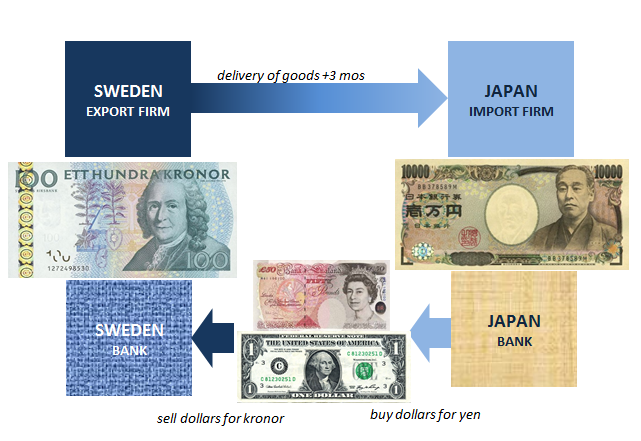

One of the first tasks of the new Federal Reserve central bank was to encourage a US dollar bankers’ acceptance market. Acceptances were a form of international money instrument, sort of a cashier’s check denominated in a common currency (primarily sterling given the UK’s dominion over much of the world and the British navy’s role in protecting commerce and trade). American authorities sought to compliment sterling acceptances with dollar acceptances so as to boost the trading power of US firms doing business abroad.

In the early days of the Fed, the institution would make a market in acceptances to such a degree that it was using them to manage total system seasonal flow (sort of like open market operations would later use UST’s to add or drain liquidity). Dollar acceptances flourished especially in the wake of gold inflows due to the WWI powers abandoning the gold standard that bolstered our currency’s international position.

Apart from those, the Fed also relaxed and removed restrictions so that US banks could begin to conduct more foreign business directly. In 1913, System regulations were changed so that National banks with $1 million in capital and surplus could establish foreign branches, subject to further approval by the Board in Washington. Only one bank chose to do so, however.

In 1916, the Federal Reserve Act was modified so that banks participating in syndicate could aggregate together the $1 million capital requirement (that was a lot of capital in those days), so long as the sole purpose of this agreement corporation, as it came to be called, was exclusively foreign banking. Only three were chartered by 1919.

In that year, Senator Walter Edge (R-NJ) sponsored a further amendment to the Federal Reserve Act that allowed for charter corporations to engage in international banking. These were called Edge Act corporations, or Edges, and for most of the next few decades they did very little and played a small role in further financial developments.

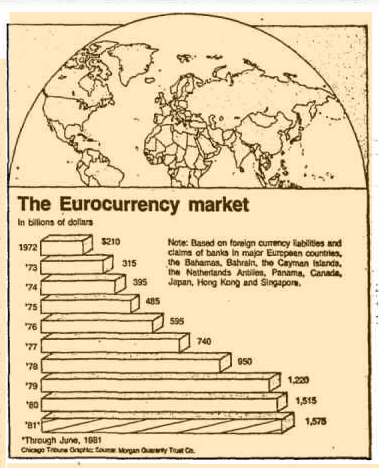

For anyone following the development of the eurodollar, it will come as no surprise that Edges suddenly became more popular in the 1960’s. Having been dormant or nearly so for forty years, there was a growing international money business where the Edge Act could finally be applied to great benefit. There were, according to the Federal Reserve Board, 38 Edges and agreement corporations in existence in 1964 (many chartered during the 1950’s) and 122 by 1976 (with $12 billion in total assets).

The benefit of any domestic bank sponsoring an Edge Act or agreement corporation was that it could conduct overseas bank business (largely) free of domestic regulations. So long as any transaction was identifiable as being international, any deposit liabilities that might be incurred would not be subject to US reserve requirements. It fit the eurodollar system’s evolving nature as giving domestic institutions an entry into it.

Having developed a window into this offshore monetary regime, several developments in the early 1980’s were crucial to opening the door for more comprehensive progression. In December 1981, eurodollar futures were introduced in Chicago at the old Mercantile Exchange. Also in December 1981, International Banking Facilities (IBF) were created in domestic law.

Taking the latter first, IBF’s allowed banks to conduct their foreign business in consolidated fashion, if not via consolidated books. In other words, banks using Edges before 1981 had to have separate offshore quarters for their subsidiary. They had to be true foreign banks with only domestic ownership. It had led to the “brassplate” offices in the Caymans, where New York or Chicago banks would have to “operate” their foreign subsidiaries in those foreign locations using nothing more than a brassplate name on an office door and a single employee with a phone connection to the home trading/funding desk.

Leave A Comment