Oil prices have fallen again: they are now at $29 a barrel for West Texas Intermediate crude and a similar price for Brent, their lowest since 2003. Natural gas, coal, and other commodity prices have also been dropping of late, in most cases. So: what will be the geopolitical consequences of cheap energy in general and of cheap oil in particular, all other things being theoretically held equal?

One geopolitical consequence of cheap energy is the weakening, possibly, of four potential great powers: Russia, Brazil, China, and Mexico. While the media has understood the Russian and Brazilian half of this list – their economies are both estimated to have shrunk by 1-3 percent druring 2015, after all, which is difficult to miss – it has largely failed to register the Chinese and Mexican half. This is because it views China as being a leading oil, energy, and natural resource importer rather than as a resource exporter like Russia or Brazil, and because it views Mexico as merely a source of drugs, migrants, resorts, and cheap goods rather than as a potential great power.

China

China may be the world’s largest energy importer, but it is has also become its second largest energy producer, and as such only relies on energy imports for an estimated 15% of its total energy consumption, in contrast to 94% in Japan, 83% in South Korea, 33% in India, 40% in Thailand, and 43% in the Philippines. In 2014 imports of oil were equal in value to just around 2.4 % of China’s GDP, according to the Wall Street Journal, compared to 3.6% in Japan, 6.9% in Korea, 5.3% in India, 5.4% in Thailand, 4% in the Philippines, and 3.3% in Indonesia. South Korea and Japan also imported more than two and four times more liquified natural gas, respectively – the prices of which tend to track oil prices more closely than conventional natural gas prices do – than China did. China’s LNG imports barely even surpassed India’s or Taiwan’s. China’s imports of natural gas in general, meanwhile, were less than half as large as Japan’s and only around 20% percent greater than South Korea’s.

China, furthermore, tends to import energy from the most commercially uncompetitive, politically fragile, or American-hated oil-exporting states, such as Venezuela, Iran, Russia, Iraq, Angola, and other African states like Congo and South Sudan. In contrast, Japan and South Korea get their crude from places that will, perhaps, be better at weathering today’s low prices, namely from Kuwait, Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia. Similarly, China gets much of its natural gas from Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Myanmar, whereas Japan imports gas from Australia and Qatar and South Korea imports gas from Qatar and Indonesia. China’s top source for imports of high-grade anthracite coal, and its third largest source for imports of coal in general, is North Korea. China has, in addition, invested capital all over the world in areas hurt by falling energy and other commodity prices, including in South America, Africa, Central Asia, Canada, and the Pacific.

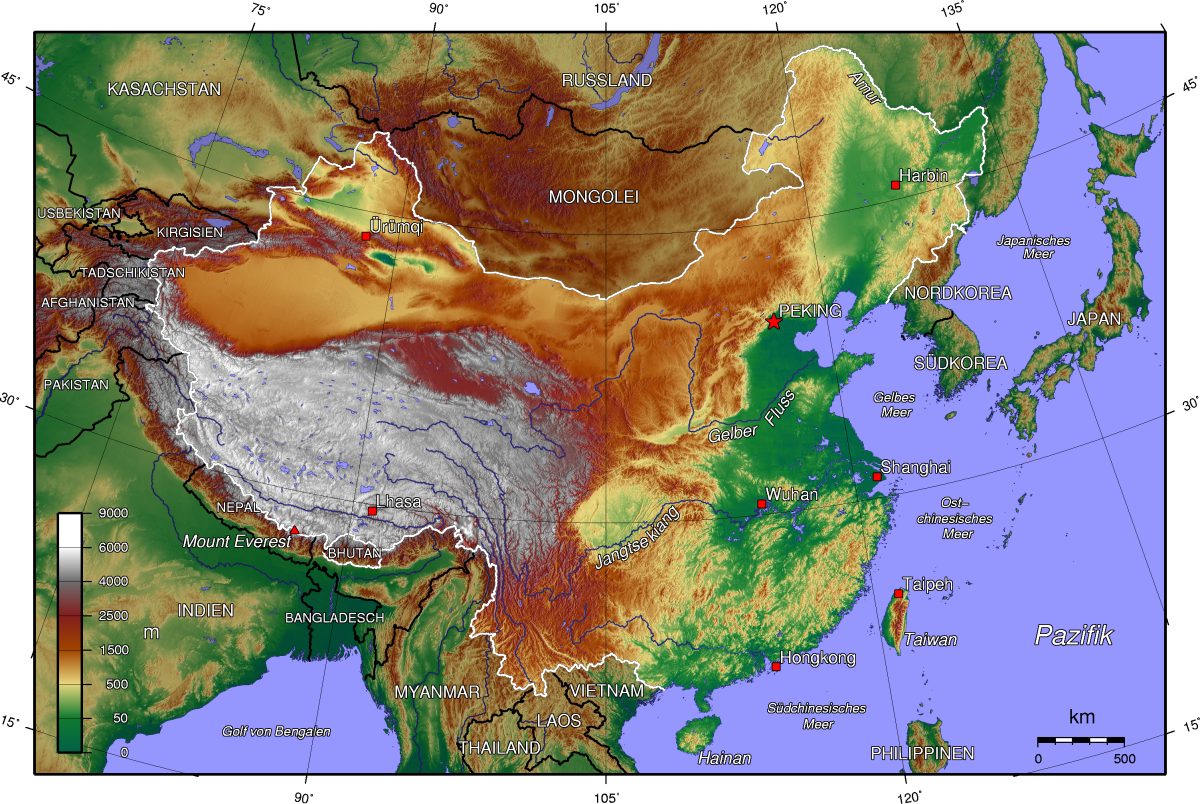

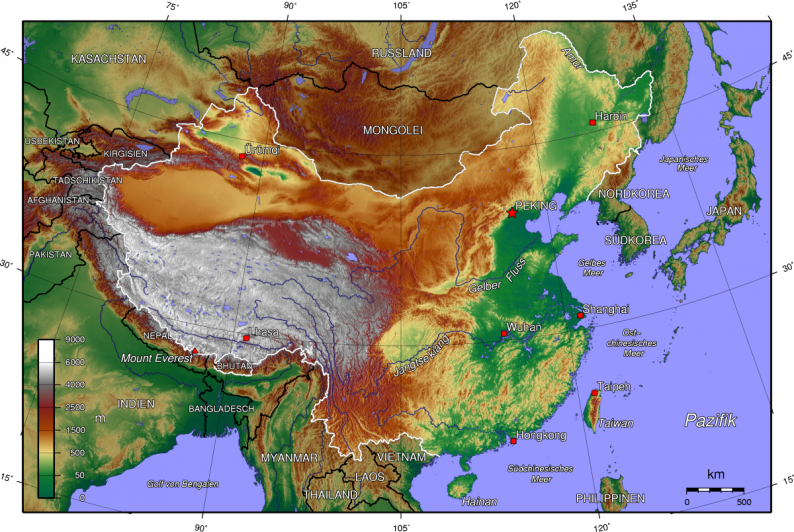

Another mistake the media makes is looking at China as if it were a country, rather than what it really is: both a country and a continent. Continents have internal, deeply-rooted regional divisions, and China is no exception. Its main divide is between areas south of the Yangtze River, which tend to be highly mountainous, sub-tropical, and dependent upon importing fossil fuels, and areas north of the Yangtze, which tend to be flat, more temperate, and rich in fossil fuels.

Northern China, stretching over 1000 km from Beijing southward to Shanghai on the Yangtze, is the country’s political heartland. It is densely populated and home to most of China’s natively Mandarin-speaking, ethnically-Han citizens. When compared to southern China, the north has historically been somewhat insulated from foreigners like the Europeans, Americans and even Japanese. Beijing’s nearest port is roughly 5000 km away from Singapore and the Strait of Malacca; Hong Kong, in contrast, is only around 2500 km from Singapore and Malacca. Beijing is rougly 2600 km from Tokyo by ship, whereas Shanghai is just 1900 km from Tokyo and Taipei is just 2100 km from Tokyo. Japan’s Ryukyu island chain and the Kuroshio ocean currents historically allowed for easy transport from Japan to Taiwan and the rest of China’s southeastern coast; the Japanese controlled Taiwan for more than three and a half decades before they first ventured into other areas of China in a serious way during the 1930s. Even today, Japan accounts for a larger share of Taiwan’s imports of goods than do either China or the United States.

Southern China has often depended on foreign trade, since much of its population lives in areas that are sandwiched narrowly between Pacific harbours on one side and coastal subtropical mountain ranges on the other. In northern and central China, in contrast, most people live in interior areas rather than directly the along the Pacific coast. These people in the interior generally did not engage in as much foreign trade, as in the past moving goods between the interior and coast was often limited by the fact that northern China’s chief river, the Huang-he, was generally unnavigable and prone to flooding northern China’s flat river plains, destroying or damaging roads and bridges in the process. In southern and central China, by comparison, even people living far inland could engage with the coast by way of the commercially navigable Yangtze and Pearl Rivers, which meet the Pacific at the points where Shanghai and Hong Kong are located.

Northern China, however, was most directly exposed to the land-based Mongol and Manchu invaders who ruled over the Chinese for most of the past half-millenium or so prior to the overthrow of the Manchu Qing Emperor in 1912. Today the north continues to retain the political capital, Beijing, and a disproportionally large majority of Chinese leaders were born in north China — including Beijing-born Xi Jinping and Shandong-born Wang Qishan — in spite of the fact that many of the Chinese political revolutionaries, including Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, Sun Yat Sen, Zhang Guotao, Chang Kai-Shek, and famed writer Lu Xun, hailed from southern or south-central China.

Today, out of China’s seven Standing Comittee top leaders, only seventh-ranked Zhang Gaoli was born in southern China, whereas five of the seven were born in northern China and one, Premier Li Keqiang, was born in central China. Zhang Gaoli may in fact be the first person born outside of northern or central China in thirty years to have made it to the Standing Committee. He is also the only person currently in the 25-member Politburo born outside of northern or central China. Among the 11-man Central Military Commission, meanwhile, seven were born in northern China, while two were born in north-central China and two in south-central China. Out of the 205 active members of the Party Central Committee, fewer than 15 were born south of central China.

Indeed, the southern half of China, stetching from islands in Taiwan, Hainan, Hong Kong, Xiamen, and Macau in the east to the plateaus of Yunnan, Sichuan, and Tibet in the west, is politically peripheral. It is home to a majority of China’s 120 million or so non-Han citizens (most of whom are not Tibetan or Uyghur, though those two groups recieve almost all of the West’s attention), China’s 200-400 million speakers of languages other than Mandarin, China’s tens of millions of speakers of dialects of Mandarin that are relatively dissimilar to the Beijing-based standardized version of Madarin, most of China’s 50-100 million recent adopters of Christianity, and most of China’s millions of family members of the enormous worldwide Chinese diaspora.

Leave A Comment