My friend and colleague, Michael Lebowitz of 720 Global Research, recently penned a response to Larry Summers commentary on the economy’s weakened ability to withstand higher interest rates. To wit:

“In his Dec. 7 op-ed, ‘Before the next recession,’ Lawrence Summers correctly said the economy’s weakened ability to withstand higher interest rates is based on the fact that lower rates in the past have pulled forward demand for goods and services, thereby leaving less demand in the future. This holds true for personal consumption, but, just as important, low rates have allowed weak, unproductive companies to stay in business and continue producing. Put these two factors together and one realizes the economy is plagued with weak demand and oversupply. Anyone who has taken a basic college economics course knows that translates into lower prices and weaker economic growth.

This is important to understand because Mr.?Summers asked how Federal Reserve policy can “delay and ultimately contain” the next recession. This long-held mentality of constant growth, with no tolerance for recession, has not allowed the economy to perform its Darwinian function and weed out excesses.

Today’s economy has a massive level of indebtedness from consumption of days past and a long history of misallocated capital that has tied up funds that could have otherwise been chasing the next great innovation and propelling our economy forward. “

Michael makes an important point that is often forgotten by the Federal Reserve’s desire to try and manipulate economic cycles.

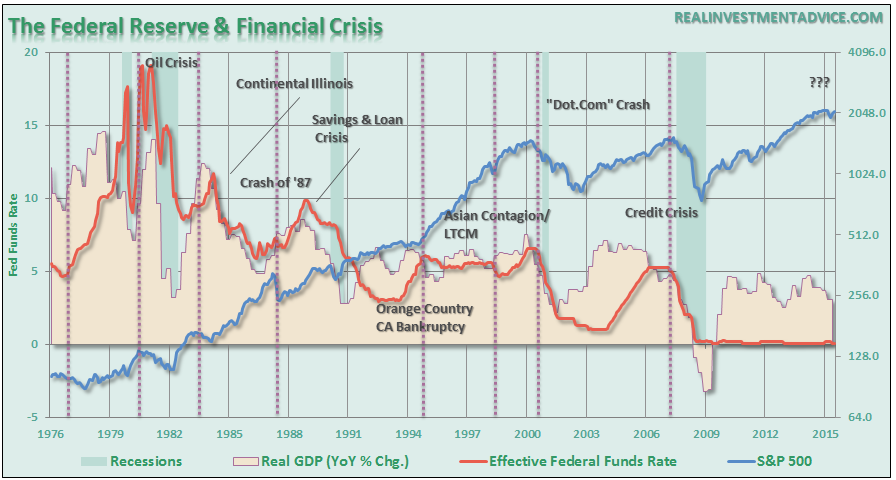

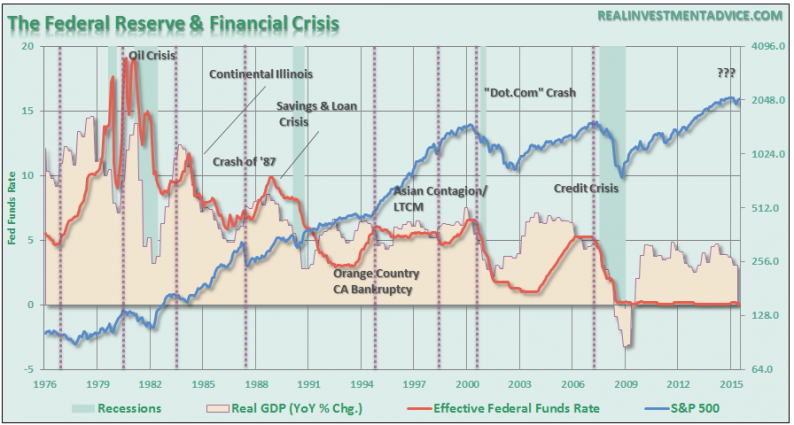

If we take a look back at recent history, it is more than just coincidence that the Fed’s not-so-invisible hand has left fingerprints on previous financial unravellings.

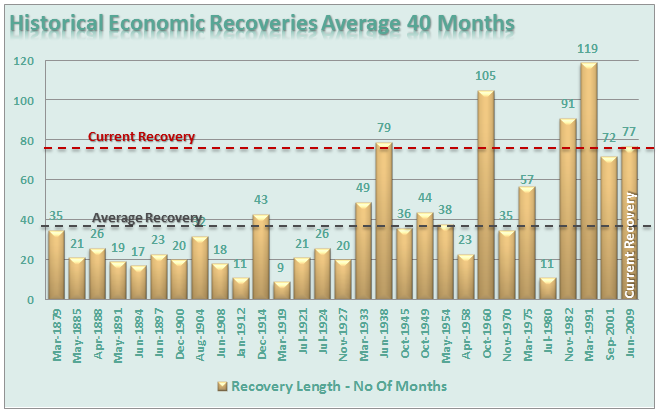

The problem for the Federal Reserve at this juncture is that despite hopes of a “recession free” economy over the next several years, the current economic cycle is already very long historical standards.

Given the years of “ultra-accommodative” policies following the financial crisis, the majority of the ability to “pull-forward” consumption appears to have run its course as witnessed by plunging rates of imports, surging levels of inventories and deteriorating profit margins even outside of the energy related sector.

Austrian’s Had It Right

According to Keynesian theory, some microeconomic-level actions, if taken collectively by a large proportion of individuals and firms, can lead to inefficient aggregate macroeconomic outcomes, where the economy operates below its potential output and growth rate (i.e. a recession). Keynes contended that “a general glut would occur when aggregate demand for goods was insufficient, leading to an economic downturn resulting in losses of potential output due to unnecessarily high unemployment, which results from the defensive (or reactive) decisions of the producers.” In other words, when there is a lack of demand from consumers due to high unemployment then the contraction in demand would, therefore, force producers to take defensive, or react, actions to reduce output.

Leave A Comment