A few years ago, most economic models presumed that interest rates were subject to a lower bound of zero. Why lend a dollar to someone who only promises to pay you back 99 cents, when you could just hold on to the dollar yourself? But we now have several years of experience from Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Japan, and the European Central Bank in which the central bank successfully induced negative interest rates in hopes of stimulating a greater level of spending on goods and services. We have enough data now to take a look at how much that seems to have accomplished, and update my earlier discussion of this topic.

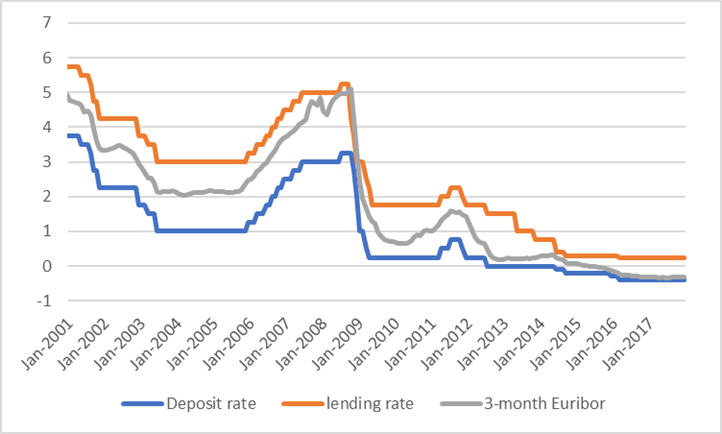

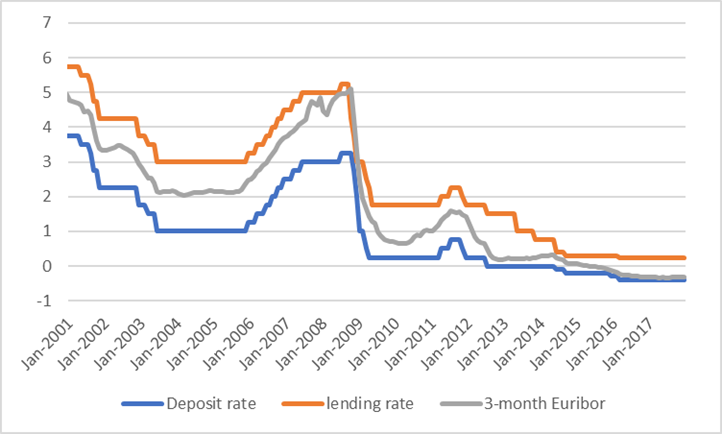

First, it’s useful to understand how the central bank could bring about negative interest rates. Consider for example the European Central Bank. Traditionally the ECB would set two interest rates: a deposit interest rate that the ECB pays to banks on excess reserves held overnight in the banks’ accounts with the ECB, and a marginal lending rate at which banks could borrow overnight from the ECB. The deposit rate would usually set a lower bound on the interest rate at which banks would offer to lend to each other– why would I lend to another bank at 2.5% if I can get 3% on my ECB deposits, which are in effect an overnight loan from my bank to the ECB? The borrowing rate likewise sets a ceiling– why borrow from another bank at 5.5% if the ECB will give me all I want at 5% through their lending facility? The graph below shows how this system worked historically, with the interest rate on 3-month loans between banks moving within the corridor specified by the ECB.

Average interest rate over the month on 3-month interbank loans (in gray) and end-of-month values for ECB deposit rate (in blue) and lending rate (in orange), January 2001 to December 2017.

The ECB brought its deposit rate all the way to zero in July 2012. When that didn’t seem to be enough, they went to -0.1% in June of 2014, in other words, charging banks a fee (corresponding to a 0.1% annual rate) on their deposits held in excess of requirements. By March of 2016 the ECB had brought the deposit rate all the way down to -0.4%, where it still stands today. Here’s a more close-up view of the most recent data. It’s functioned just like the historical system, with banks lending to each other at a rate that is somewhere between the deposit rate (currently -0.4%) and lending rate (currently +0.25%). The average rate on interbank loans for December turned out to be -0.33%.

Leave A Comment