The level of debt owed by African governments in countries such as Kenya, Uganda, Mozambique, and Tanzania has increased markedly since the 2008 financial crisis. Problematic though sub-Saharan African debt may be, debt levels vary country by country and therefore mitigate the possibility of a continent-wide crisis. Still, widespread default could create opportunities for outside powers that covet the region’s natural resources.

How It Happened

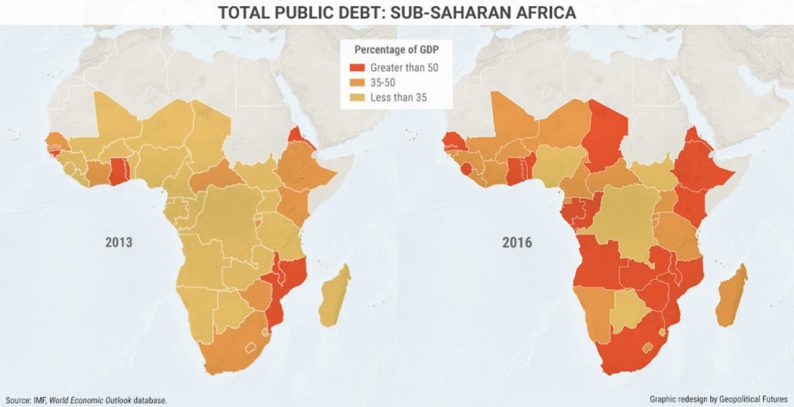

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, global interest rates were low, and money was cheap. Investors who sought greater returns turned to riskier investments, including African sovereign debt. Countries across the continent took on debt to fund infrastructure and other development projects. Countries such as Nigeria and Botswana still have debt burdens of under 50 percent of GDP—the level at which debt is generally considered high for developing countries. Other countries such as Mozambique and South Africa have debt burdens of more than 100 percent of GDP. Median public-sector debt in sub-Saharan Africa was 48 percent in 2016.

Source: Geopolitical Futures

The current situation resembles the African debt crisis of the 1980s. In the time leading up to the debt crisis, many sub-Saharan African countries similarly took advantage of lower interest rates and took on more debt. When Western central banks raised interest rates to combat inflation, the cost of servicing this debt grew. The fact that many of the loans were denominated in foreign currencies made things worse. When interest rates in the United States went up, the dollar appreciated relative to local currencies in sub-Saharan Africa, making repayment even costlier. Meanwhile, the price of the commodities on which so many of these countries depend fell, decreasing the amount of money they had to pay back their loans.

Over the past 10 years, amidst an environment of low global interest rates, African governments have likewise accumulated more debt. As the US and EU economies recovered, central banks have begun to raise interest rates. As much as 70 percent of this debt is denominated in foreign currencies, according to S&P, though the figure is much lower for Nigeria and South Africa, which together constitute a large portion of total sub-Saharan African debt. A decline in global demand for commodities—say, if China were to enter a recession— would once again put pressure on these government revenues, many of which are still dependent on natural resources.

Leave A Comment