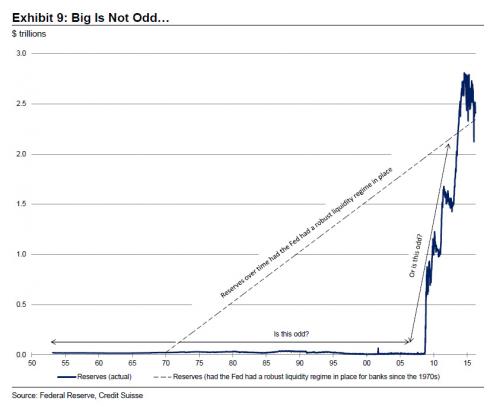

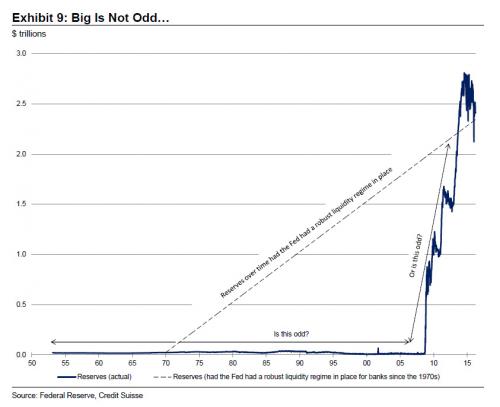

Back in early April, one of the foremost experts on the practical applications of QE (there are many more “experts” on the discredited theoretical framework of QE, most of whom are career economists), Credit Suisse’s Zoltan Pozsar wrote a note titled “What Excess Reserves”, in which the former NY Fed analyst made a very clear case for why the Fed’s balance sheet will never shrink again (particularly in the context of the broken Fed Funds market). Some of the note’s highlights:

Instead of asking when the Fed will shrink its balance sheet, it’s about time the market gets used to the idea that we are witnessing a structural shift in the amount of reserves the U.S. banks will be required to hold, where reserves replace bonds as the primary source of banks’ liquidity. And that this shift will underwrite demand for a large Fed balance sheet.

Back in April, ge also laid out the role of the Fed’s massively expanded balance sheet in the context of the prime money fund shrinkage as a result of the October 14 money market reform deadline:

[W]e are witnessing a structural shift in the amount of reserves held by foreign banks as well. Gone are the days when foreign banks settled their Eurodollar transactions with deposits held at correspondent money center banks in New York. Under the new rules, interbank deposits do not count as HQLA, and foreign banks are increasingly settling Eurodollar transactions with reserve balances at the Fed. Foreign banks’ demand for reserves as HQLA to back Eurodollar deposits and as ultimate means of settlement for Eurodollar transactions will underwrite the need for a large Fed balance sheet as well. Prime money fund reform is a very important yet grossly under-appreciated aspect of this, one with geo-strategic relevance for the United States.

Prime money funds have been providing the overwhelming portion of funding for foreign banks’ reserve balances. If the prime money fund complex shrinks dramatically after the October 14th reform deadline, funding these reserve balancees will become structurally more expensive. This in turn means that for foreign banks across the globe running Eurodollar businesses – lending Eurodollars and taking Eurodollar deposits – will become structurally more expensive. Why? Because if the LCR requires banks to hold more reserves as the preferred medium for settling Eurodollar transactions and the funding ofthese balances become more expensive, funding the liquidity portfolio corresponding to Eurodollar books may become a negative trade. Will that somewhat diminish the dollar’s pre-eminence as the global reserve currency and play into China’s hand? You bet…

Leave A Comment